Chapter 9 - Part 1: Cycling Cyprus, Two Realities

Greek and Turkish Cultures Mix and Collide

Cyprus: First Lessons

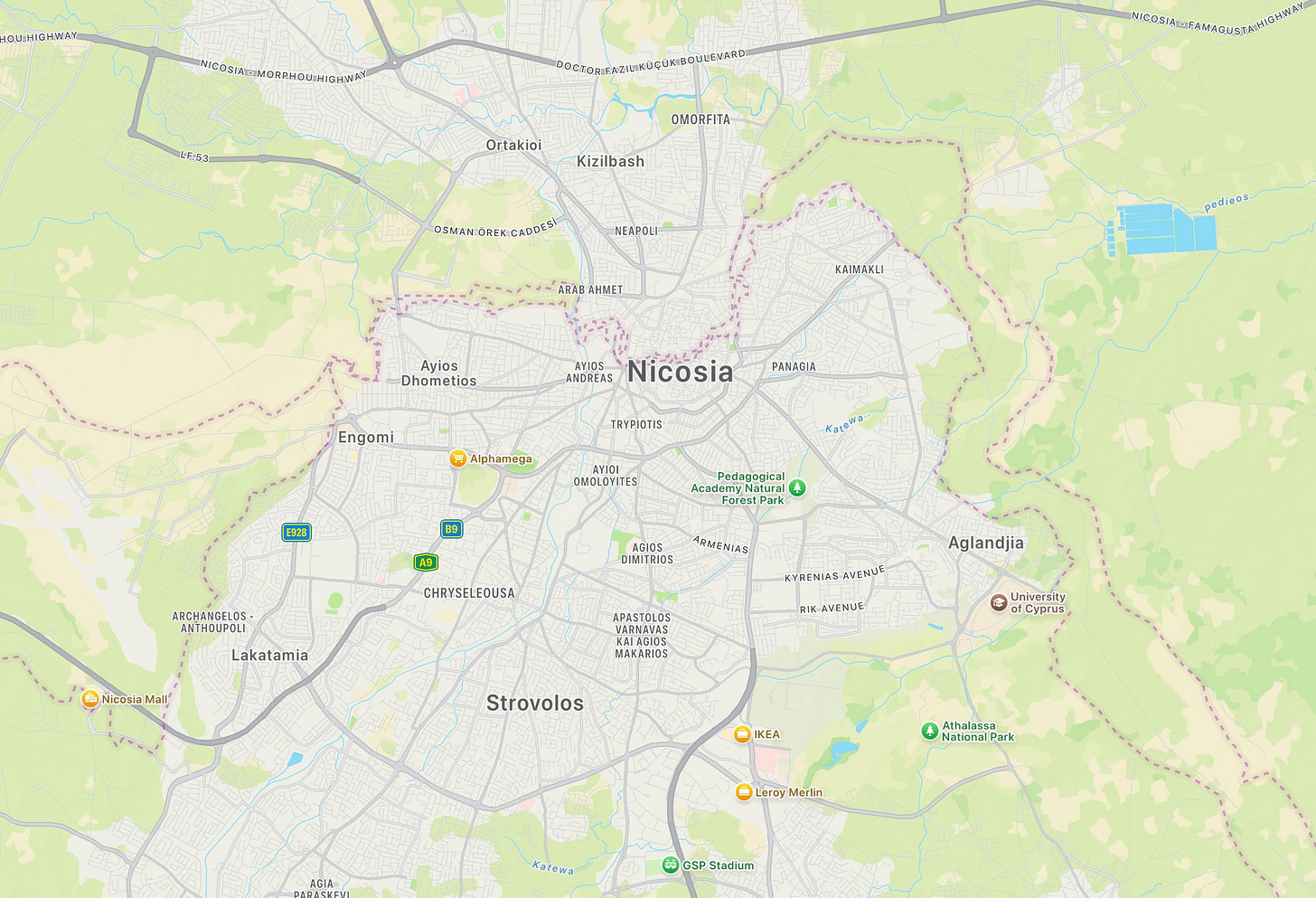

We ride our bikes about 40 miles inland from Larnaca (where the airport is located - see satellite map, below) on the southern coast, into the affluent and bustling Greek-side of Nicosia, in central Cyprus. After leaving the bike path in Larnaca behind, it is a pleasant journey to Nicosia, with a mix of hilly pavement and gravel.

Passed with good etiquette by a small group of young English-speaking Russian cyclists (recreational racers), they engage us in conversation while riding adjacent for 5 or 10 minutes. They do not see many bikepackers or bike tourists here, and are curious about our plans. Cyprus has historically had a sizable Russian population, both vacationers and full-timers; indeed, many shop signs and billboards exhibit Cyrillic lettering. To my untrained eye, it is initially difficult to distinguish Greek Russian.

Our first night in Nicosia is spent on the Greek-side, in what turns out to be a very modern and large third-floor apartment, rented-out by an older, retired couple living on the first floor. It costs just $45.00/night, a very reasonable price. Indeed, accommodation costs in Cyprus (both north and south) are uniformly on the low side.

We eventually wind our way through the busy, narrow, and moderately dangerous (from a cycling point of view) streets of Greek Nicosia towards the UN-controlled buffer zone -the “Green Line” - carving Nicosia in two, trying to find the correct pedestrian entry point - passport control - to the Turkish-occupied north. There is freedom of movement between the two zones, but you can’t just waltz in.

The streets are very narrow near the crossing point, with much evidence of relatively recent rebuilding - new cobblestones, new shops, nice lighting. European Union, Cypriot, and Greek flags and decals are everywhere.

It reminds me somewhat of urban renewal architecture that one sees in small downtown areas in the US, except the reason for the rebuilding was a war-inflicted frenzy of utter destruction just 50 years ago. In any event, we wander towards what looks to us like a possible entry-point; there is a door and fencing with old and rusted barbed wire.

While straddling my bike, I politely ask a soldier, who I later learn is probably a Slovakian peacekeeper, if we can cross into the Turkish sector at this location. He says, with a sense of humor in very broken English, that yes, I could go through this location, but he would have to shoot me if I tried. He points vaguely to an adjacent area where a passport control building is apparently situated.

I didn’t really think he would shoot me, but his banter is reflective of the dead seriousness with which UN peacekeepers comport themselves in this post-war zone. As we turn our bikes around, a very old Greek woman dressed in black opens a beautiful, blue wooden door, sticks her head out, and tells us that the soldier should not have said that to us, even if he was “just kidding.” She shakes her head with rank disapproval and gives us more detailed directions to passport control, mostly in Greek, sprinkled with English words, through the labyrinth of narrow streets. This is old Nicosia, and it is tight, compact, and feels somewhat claustrophobic. I can imagine it must have been terrifying when the bullets and bombs were flying in this area.

We do ultimately find what can only be described as a forlorn border crossing post separating the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot sectors of Nicosia. Two lines of entrants form, one for Cypriot passport-holders (both Greek and Turkish) and one for foreigners. Because the Republic of Cyprus (ROC) is an EU country, as US passport-holders, we were stamped in for 90 days at the Larnaca airport. I am unsure how much time we will be given in the Turkish-occupied north (also known as the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) (recognized as a country only by itself, and by the Republic of Turkey - since 1983).

We present our passports through a smokey window (the officers are smoking inside the building) to the saddest and most bored customs officer we have ever seen or met. I realize that these civil servants, everywhere, are not paid to be nice and cheerful. That is not their role. Nevertheless, we cannot help but feel sorry for her. She is about 30, wearing a nice uniform. Barely looking up, she runs our passports through some sort of ancient computer check and stamps us into the TRNC for 90 days. No eye contact, no questions asked. I have nothing to complain about. As we are leaving the EU, we are also leaving the euro, and entering the diminished currency world of the Turkish lira. As it turns out, though, the TRNC (we are glad to find) is financially connected to the outside world, and our credit cards work well with the mobile payment devices held by almost all the vendors we meet in the north. Many merchants also accept euros and dollars.

Crossing the border is a jarring, but not unpleasant, experience. It is somewhat similar to how a US citizen might feel entering Mexico from California - the relative affluence of the Greek ROC abruptly ends, and the economic realities of life in the isolated TRNC begins. More on this below. The difference in standard of living is not as pronounced as that between the US and Mexico, but it is noticeable nonetheless, especially in terms of infrastructure.

Turkey provides huge amounts of economic aid to its brethren in the TRNC (about $400 million each year), and much of it ends up here, in its capital of northern Nicosia. In addition to economics, one leaves behind a Greek Orthodox world, and enters a Muslim world - a call to prayer - the first of many (five times/day) is heard almost immediately upon crossing-over. This is the second Muslim country we have been to, the first being Malaysia. Northern Cyprus does not have a strictly pious religious culture; many women are out and about without hijab, and Pam is fine without a head covering throughout the north. She does cover her legs from time to time while riding.

Cyprus: A Little Background (it gets complicated very quickly)

We knew very little of Cyprus before arriving here on December 1, 2024. My prior research revealed that its winter is warm, and that there would be beaches, mountains, and nice small cities. Plus, although a member of the EU, it is not (yet) a part of the Schengen Zone, and is therefore a safe haven for us to continue traveling after the expiration of our 90-day visa-free travel within the Zone. We considered Turkey, Bulgaria, and a few other places that are not in the Zone as places to explore for another 5 or 6 weeks, but Cyprus seemed to check all of the desired boxes.

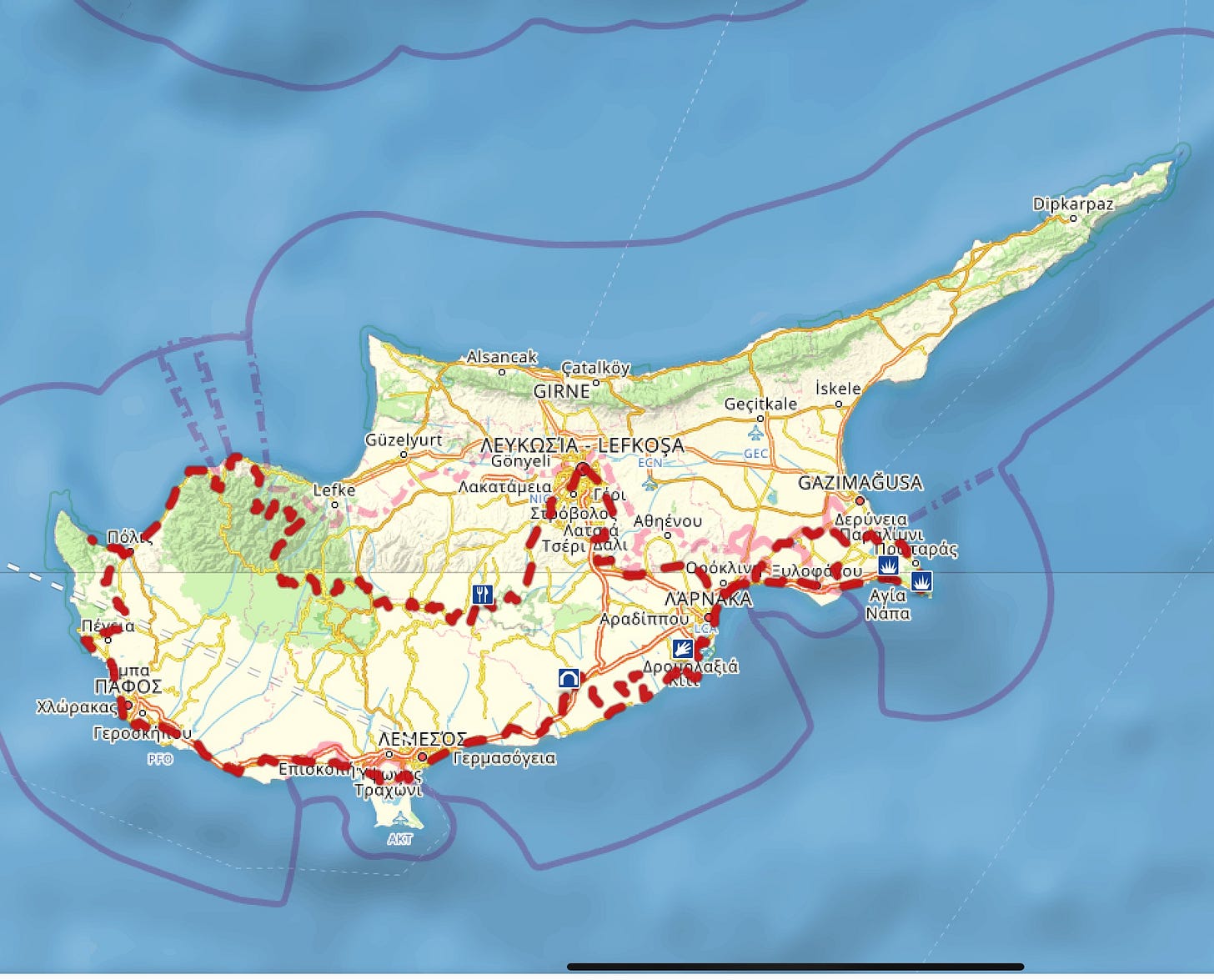

From a cycling perspective, although the available information is sparse, I am aware that the EuroVelo 7, the same route we had followed in Greece, extends to parts of Cyprus. We also see from our mapping apps that Cyprus is crisscrossed by many dirt and gravel roads, as well as seldom-used paved roads extending to all parts of the island. Most of the cities in the south, and some in the north, seem to have bike lanes that enter and exit densely populated areas. The land mass includes some big, wooded, mountains, mostly in the south (10,000 feet-plus - ice and snowfall are common). Many other areas are relatively flat, with some coastal hills in the north.

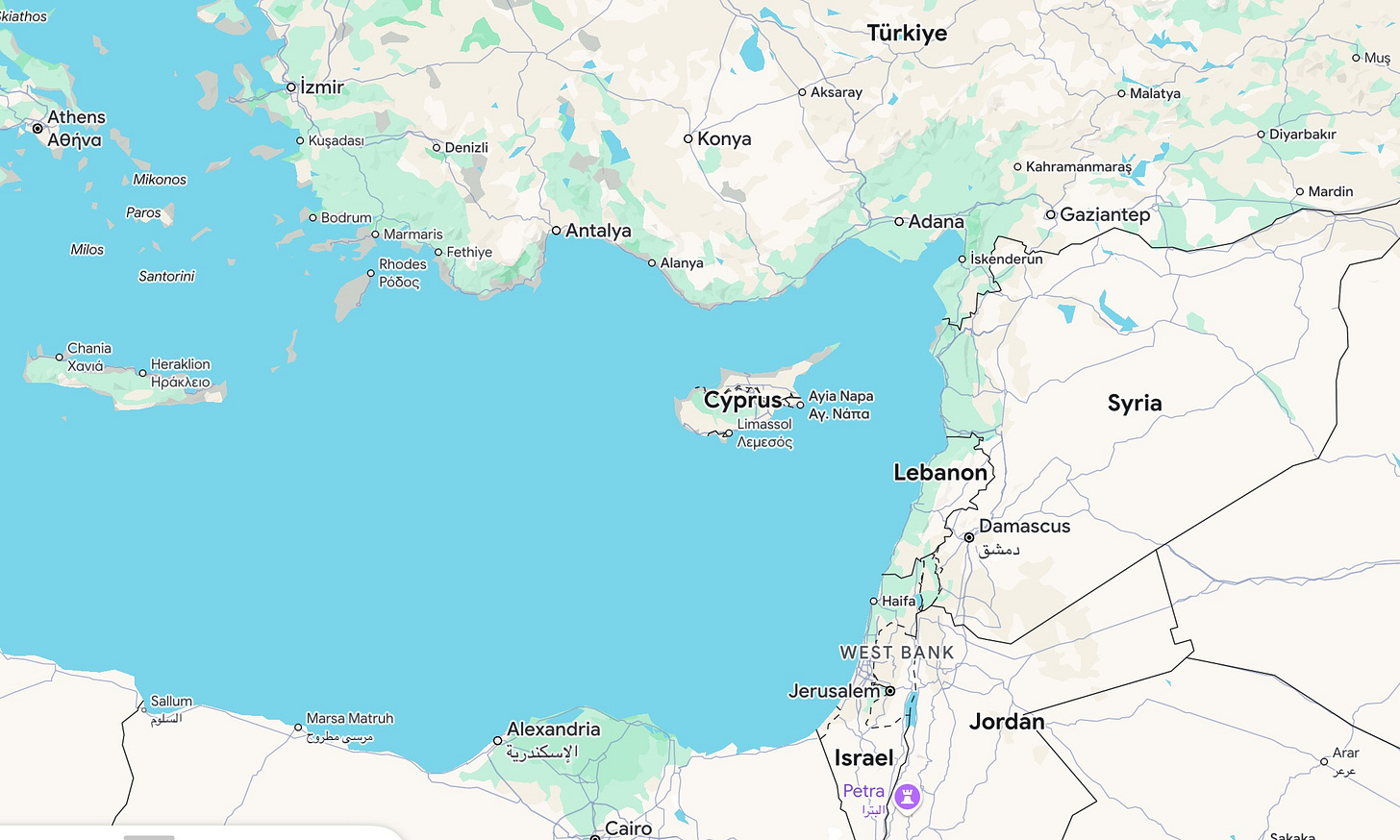

The island is quite small, just about 3500 square miles. By comparison, the US State of Connecticut is 5500 square miles, and the State of Israel is 8600 square miles (including inland water bodies). The ROC comprises 63.7% of the land mass, the TRNC 36.3%, and UK Sovereign Base Areas (British military bases) 2.7%. The UK has a presence on the island, separate and distinct from that of the UN.

The total population of Cyprus is 1.25 million. The ROC’s share is about 925,000, or 74% (mostly Greek Cypriots, but also almost one-quarter foreign nationals), while the TRNC is comprised of about 400,000 people (26%), with 60% Turkish Cypriots, and 35-40% Turkish “settlers” from Turkey. The TRNC also has a high number of temporary residents, especially students (from Turkey and a few African countries - mostly Nigeria) and foreign workers, most of whom seem to be from Bangladesh.

It’s a complex mosaic, and one can see a fundamental problem in the numbers, above. The ROC has 3/4 of the population, but less than 2/3 of the land mass (63.7%), while the TRNC has a little over a quarter of the population, but more than 1/3 (36.3%) of the land mass. This is a source of real irritation on the part of the ROC and Greek Cypriots, and is a residual issue from the 1974 war and ongoing Turkish military occupation in the north.

A large population transfer/exchange took place after the 1974 war, with thousands of Turkish Cypriots moving from the south to the north, and thousands of Greek Cypriots moving from the north to the south. The British Sovereign Bases played a key role as refugee resettlement areas in making this happen relatively peacefully. More on this below, and in future posts.

Interestingly, there is ongoing litigation in Cyprus between Greek Cypriots who lost land in the north, and the Turkish government (who appropriated and then redistributed that land to Turkish “settlers” and Turkish Cypriots). Indeed, some claims have been paid by Turkey with potentially big financial implications..

We are less familiar with the vast economic, religious, and cultural differences that still exist between the Turkish north and Greek south, differences that have prevented reunification 50 years after the end of armed conflict. We learn a lot quickly, and it is a source of discussion, with someone, almost every day.

I learn that Cypriot history can be read in many ways, and is read quite differently depending upon whether you are a Turkish Cypriot or a Greek Cypriot. Perspective is everything. But I am a firm believer in facts and reality. So here is my non-expert, very brief, hopefully unbiased, preliminary take.

The Ottoman Empire (i.e., Turks from Turkey) conquered Cyprus in 1571. The island, although overwhelmingly Greek-speaking and Greek Orthodox in religious orientation (90-95%), was at the time run by the Venetians (yes, from Venice, a Republic in what is now Italy). Given the close proximity of Turkey to Cyprus, an in-migration of Turks onto the island occurred. Over time, a Turkish Cypriot community developed - not only in the north - speaking Turkish and practicing Sunni Islam. By the 1700 - 1800s, Turkish Muslims comprised upwards of 15% of the population. This percentage would double over the next couple of hundred years. The island was also home to small populations of Jews, Armenians, and Maronite Christians. We saw one synagogue (in Larnaca) and several Armenian and Maronite Churches sprinkled about both the north and the south.

The Ottomans maintained control until 1878 when, due to a complex set of geo-political facts involving Russia, Turkey and the UK, the Ottomans leased the island to the UK, but retained technical sovereignty. Cyprus at that time magically became a British “protectorate.” As the Ottoman Empire continued to unravel during the early part of the 20th century, and the Ottomans entered WW I opposed to the UK, the British formally annexed, or captured, the island. Turkey later formally recognized British sovereignty in 1925, and Cyprus became a British Crown Colony. Ok, that’s enough history, politics, geography, and demographics for now. All of these factors, though, affect to one degree or another, our bike tour of the island.

Turkish-Occupied Northern Nicosia

After proceeding through passport control, we walk our bikes through a touristy market area featuring inexpensive souvenirs and clothing. We immediately encounter mosques, Turkish flags, Turkish monuments, Turkish bakeries, hookah bars, Turkish language, and old cars (reminds me of pictures I have seen of Cuba). There are fewer large, modern, grocery stores and, to our dismay, fewer coffee shops - actually almost none. I do start drinking Turkish coffee, which is often not bad. Pam does not. We had grown fond of the coffee in Larnaca and Greek Nicosia. A minor point.

The two guys ahead of us in line ask about our bikes and what we are up to. They are off-duty UN peacekeepers. One happens to be the Irish Deputy Commander of the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus. He is a colonel, and has been stationed here for several years. The other is his mate from the UK. They are both quite affable, and we have a fascinating, quick, conversation; both Pam and I have lots of questions about the “situation” and the role the UN is playing. I told him he was just the person with whom I wanted to speak.

We learn that the armed peacekeepers along the 112 mile Green Line resolve sometimes heated and complex disputes on the ground every day about all sorts of things, some minor, some major. There are lots of moving parts to keep track of, including the management of military and police personnel from 29 different countries, spread across those 112 miles. Turkish troops are also present in some areas north of the Green Line (it is actually a buffer zone that varies considerably in width), and Greek Cypriot soldiers are present south of the line. Hovering drones from both sides can be seen along the border, especially at night. After about 10 minutes of chattering, we wish each other well, and part ways.

Because Cyprus is a small island, and we have plenty of time, we need not cover huge distances on a daily basis. Our riding levels out to about 30- 50 miles each day that we do ride, with every fourth or fifth day for rest, plus some extended stays in certain areas. We ultimately cover most of the island.

Our accommodation is a small hostel not far from the border crossing. Instead of Greek lettering, all signage is in Turkish, with a smattering of English and Russian. Our mapping apps nevertheless work well, and we easily find the hostel. It is located directly adjacent to the large mosque under renovation, pictured above. Indeed, both the hostel and the mosque are undergoing significant rehab, and dust is everywhere.

We are greeted by the owner of the hostel, Barcin, a 50-something man clearly in charge of the construction. The place has a surprisingly bohemian feel to it, and we soon meet other guests in a central sitting area, which includes a piano, guitars and various drums. They are from Germany, the UK and Switzerland. I can almost touch the historic mosque next door from our second floor window. A call to prayer blasts into our room from a nearby public address device that broadcasts in all directions.

Barcin is from Nicosia, but went to University in Istanbul to study urban planning. Living in Istanbul for 20 years, he also studied English, and his language skills are good. Unfortunately, urban planning did not work out and, returning to his home in Nicosia, he became an “event organizer” and DJ. He loves world music, and hosts “multicultural parties.” His hostel will also soon include a cafe bar where he hopes to promote inter-cultural dialogue.

Barcin was a young boy at the time of the civil war in the mid-70s, and has lived his entire life in a divided world. And he clearly does not like the current situation. He understands that the TRNC is isolated politically and economically, making life difficult. Barcin is, through his hostel and cafe, trying to bridge the gap among cultures and would like to see the island reunified, but not at any cost. We also learn more about the nuances of life in the TRNC; for example, the Turkish “settlers” from Turkey (arriving post-1974) have their own cultural identity distinct from the Turkish Cypriots. Turkish Cypriots have their own Turkish dialect, music, dance, cuisine, and island identity. Turkish Cypriots tend to be more secular and cosmopolitan than their settler cousins, who hail from generally conservative rural areas of Turkey, and take a more nationalist political stance. We are unable, on our own, to really ascertain these subtle cultural divisions among the northern Turks. Barcin’s insights are very much appreciated.

Nevertheless, significant residual (if not habitual) animosity between Greeks and Turks on the island remains, although movements are afoot, especially among younger generations (of which Barcin is a part) to forge Turkish - Greek relationships and eventually re-unite the country. This would certainly benefit the north as it would then become part of the EU. A complicating factor is that Turkey is not part of the EU, and has essentially been denied membership over the years for a variety of reasons well beyond the scope of this post.

I tell Barcin that I have been reading quite a lot about Cyprus, and he is very interested in exactly what I have been reading, wanting me to get an unbiased picture. He has a bookshelf full of books about Cyprus, the wars (both the war of independence fought against the UK in the 1950s, and the civil war between Turks and Greeks in the mid-1970s), and various Cyprus-themed novels, and I take note of the various titles. I would recommend one novel that I read, in particular - The Island of the Missing Trees (by Elif Shafak). This book, very well-written, captures the overall sensibility of the island while also providing an accurate and sensitive historical backdrop. Recent traumatic history permeates everything and everyone here in Cyprus - it is never far from the surface.

We leave early the next day. Because the rooms are on the second floor, up a set of narrow and windy stone steps, we have kept our bikes downstairs tucked under the staircase. Barcin lets us out (the door is, unusually, locked from both the outside and the inside) and we say our good-byes. He hopes we will enjoy the north and tells us that the cafe will be finished in two weeks, inshallah, and to please return and say hello.

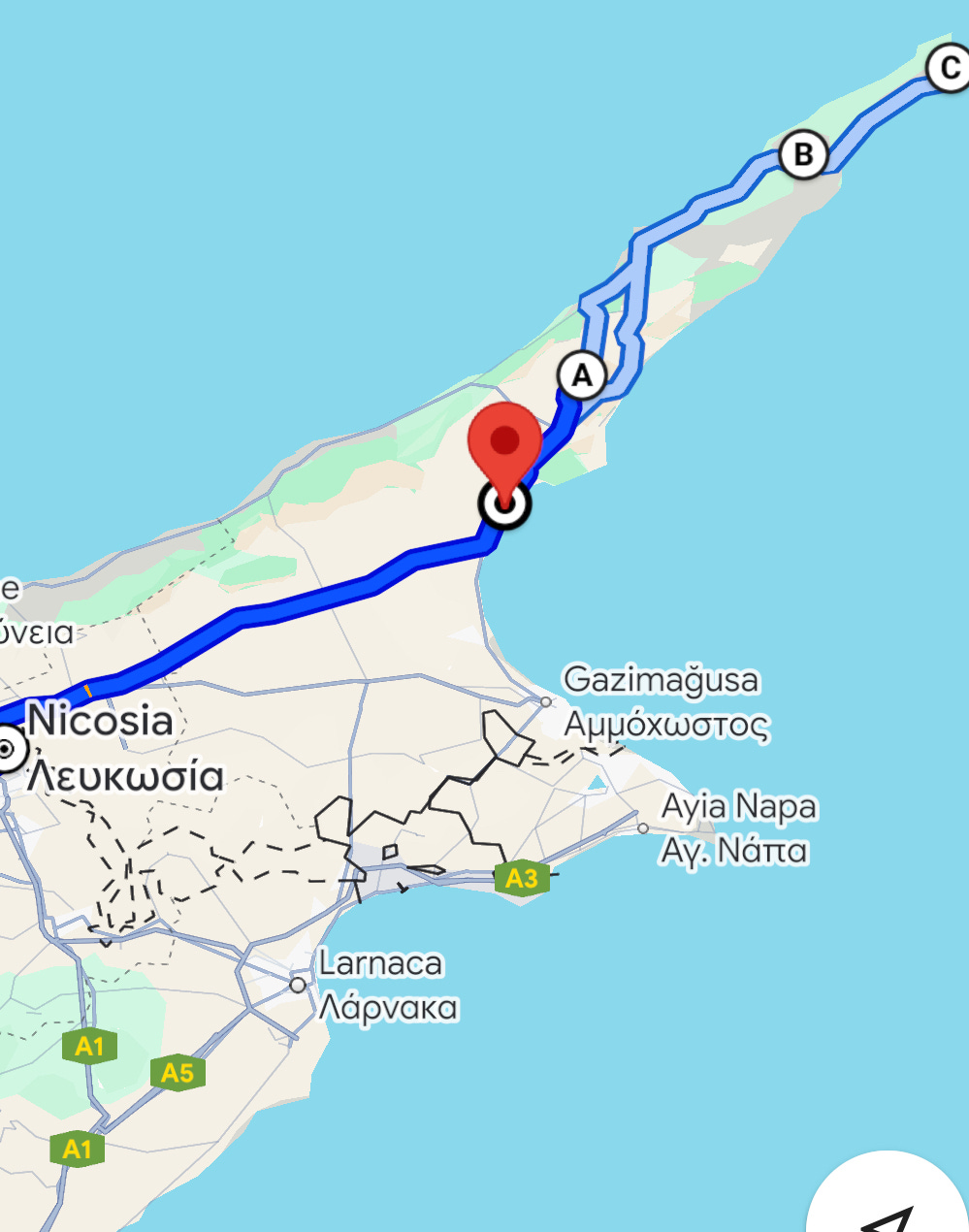

Biking from Nicosia to the Karpaz Peninsula

It is New Year’s Day 2025 as we ride out of northern Nicosia. The road is busy and dusty. Drivers are very friendly and courteous, but clearly do not see many cyclists. Similar to our initial experience in the south, cycling is not a common mode of transportation. Travel is almost exclusively cars, busses and trucks driving on severely overburdened roadways. We seek out sidewalks and lesser-traveled roads wherever they exist, but the road system is not that extensive. It does not take long to reach the outskirts of the city, where houses give way to a relatively expansive, flat plain. One of the first things we see out here, though, serves as a reminder that all is not completely normal.

We quickly arrive at the impressive Hala Sultan Mosque. The building of the mosque was funded by Turkey, and I later learn that Turkish President Erdogan attended its opening in 2018. It holds up to 3000 worshippers inside. As we ride through the area, we see that the mosque is also part of a larger area of development that includes a branch of the University of Ankara. College students are busy going about their business. The roads improve considerably in this area, as it is new development. We pedal through the crowds of young people attending classes. We are heading in the direction of Bogazi on the coast, where we hope to spend a couple of night checking out the beach scene.

We ride on through a semi-agricultural area towards a town where we can safely refill our water bottles (the water out of the faucet is generally not potable in Northern Cyprus). Not far from the huge, new mosque, we are once again in large fields of vegetables, interspersed with buildings in various stages of decay.

The road takes us through a number of small villages, and we stop at this one (in Gecitkale), covered in umbrellas:

It is quite late in the day when we arrive in the coastal town of Bogazi. This area, now under intensive resort development, was inhabited predominantly by Greek Cypriots prior to 1974. Many of the Greek Cypriots fled south after the war in 1974, leaving prime beachfront real estate. The property along the coast has since been repopulated by Turkish Cypriots and Turkish settlers from Turkey. Although I don’t usually book into large high-rise resort hotels, the options are limited and the prices very low in the off-season.

An elegantly dressed Nigerian woman checks us in. Her first language is English, but she also speaks some German and Russian. She tells me that many Russians come here during the high season, sometimes staying for extended periods, so Russian language helps. A young Bangladeshi man helps us maneuver our dusty bikes into an elevator that will take us to the 8th floor. He has been in Northern Cyprus for almost one year, working in the resort as a jack-of-all-trades with other Bangladeshi workers. He sends money back to his family in Bangladesh every month.

We do wonder where all the money comes from to build these giant resorts. and whether it is legit, or not. Russians? Turks? Brits? A little internet sleuthing reveals that our hotel complex here in Turkish Northern Cyprus was built, and is apparently owned, by an Israeli billionaire. Side note: many Israelis have long-visited Cyprus as tourists given the close proximity to Israel, mostly in the south. Some stores cater to Israelis and are kosher. In any event, our billionaire, had been arrested just a week earlier in the south by Republic of Cyprus police in connection with unspecified financial crimes.

I learn that Northern Cyprus has a (well-deserved) reputation for money laundering and financial opacity, despite a well-developed common-law legal code inherited from the British (modified somewhat by Turkish law). I’m sure being a lawyer here cannot be easy. The TRNC is not part of international financial bodies like the IMF or World Bank. As a result, there is very little banking supervision or rules-based enforcement. Local regulation is also weak. Northern Cyprus is a society with its feet in two worlds - the island and Turkey. The line between legality and illegality is therefore a moving one, especially when large sums of money are at play. What could go wrong? The TRNC’s political and economic isolation comes with a price. It is not surprising that shady real estate deals have become common, and casinos - money laundering centers - flourish.

We explore the beach and find it quite muddy and, even if it were warm enough, not really swimmable. A development of smaller beach houses sits in front of the towers, with immediate sea access. A wooden path has been laid across much of the beach to facilitate walking over the mud. It seems the sea is seeping inland. These bungalows are older, and not in the best of shape. I suspect they may have been here since the 1970s, holdovers from when the area was a Greek beach resort.

After a couple of days of luxury living, we hop bike on the bikes and head into the interior of the Karpaz Peninsula. Getting to the very tip by bike is not a straight line ride. We also discover that our maps often do not account for large Turkish military bases that dot many areas in the north.

Pam is working hard to get us to a less-traveled dirt road. We make a turn, and encounter many signs, all in Turkish, that I surmise are telling us “stop, you do not belong here.” The road, though, is in great condition (of course - it’s a military base). We do spy a gate ahead with a couple of late-teen soldiers manning the fort. At the very least, we can ask them where we should go.

We manage to cause quite a commotion, as I do not think they get too many bikers, especially of a certain age, wandering up into their military base, which I later learn probably houses numerous drones. The teens do not speak any English, but we do catch their drift - we must go all the way around the base, which is fenced-in for miles. Finally, a small group of slightly older officers come out and engage. One speaks some English, and clarifies that under no circumstances could we go through the base to our desired connecting road; instead, we had to back track and go around. He does ask us where we are from, and when I say the US, he seems relieved. We show him our mapping app, and he is actually quite helpful with directions. The soldiers seem, on the whole, amused by the encounter, and we all wave good-bye with smiles.

I am struck by the number of large military installations in Northern Cyprus, all housing Turkish troops and equipment. They do not improve the aesthetics of the region. Their fences interrupt farmland and divide towns and cities. It is not just the one described above; they are plopped down into many areas (both urban and rural), and are off-limits to everyone except the 40,000 Turkish soldiers stationed here. Northern Cyprus is often referred to by people living in the ROC as Turkish-occupied Northern Cyprus. Indeed, I think that is accurate, but the Turkish troops are now occupying land that would otherwise be used by the Turkish Cypriots.

Although I am sure many Turkish Cypriots think of the soldiers as saviors and brothers, at this point, 50 years after the war, I would also think that at least a few would not mind if the soldiers went back to Turkey, and allow the land they are occupying to be used for peaceful purposes. How about a mountain bike park? I could certainly be wrong about this, but I do wonder if Turkey would leave voluntarily, even if asked to by the Turkish Cypriots as part of a negotiated settlement. The UN Green Line could be maintained to keep the peace. A repeat of the events of 1974 is unlikely. I heard more than one disgruntled Greek Cypriot refer to the north as Turkey’s newest province, and they might not be wrong.

Biking around the perimeter of the base, we see a few mountains ahead, and all of a sudden we are climbing. A very distinctive Turkish military monument can be seen in the distance and are route will take us in that direction.

We have lunch at this little roadside stand, buying some very fresh olive bread. I learn the hard way that the pits are not removed from the olives as part of the bread making process.

We enter what I later learn is one of the “breadbasket” regions of Northern Cyprus. Much produce is grown around here (the village of Mehmetcik) but it is best known for its grapes and wine. A large grape and wine festival is held every year.

The hotel we are staying at tonight in Mehmetcik, the Celebi Gardens, is virtually empty. The kitchen, though, is open and we have a very good Turkish meal of lamb chops and soup. The place is owned by an older couple, but run by their very friendly daughter. We speak with her and learn she attended business college in Istanbul and decided to come back here to run the family business, a very common scenario. The hotel sits overlooking the grape-growing valley below, and offers a spectacular view at sunrise:

Before the 1974 war, Mehmetcik, was known as Galateia, and was almost entirely Greek. The Greek residents fled to the south, and the village was then resettled by Turkish Cypriots fleeing from the south to the north, and by Turkish settlers from mainland Turkey. Interestingly, the name of the town in Turkish - Mehmetcik -means “little Mehmet” - a term of affection for Turkish soldiers. One can see why the original inhabitants of this beautiful village, and their descendants, might want to return here, and are resentful about the “situation.”

NEXT TIME: Cyprus, Part 2. Cycling the Karpaz Peninsula, feral donkeys, the north coast, the Greek south, Famagusta, dark tourism. Cats. More Cypriot history.

Wild donkeys dominate the outer Karpaz

Paphos, Republic of Cyprus

Riding in the Akama National Park, Republic of Cyprus

Fantastic, good reporting… I’m jealous

Thanks, Bill